Our Engineering Process

What is an iteration? An iteration in the engineering process is where you stop, take what you have learned to date and revert to an earlier step in the process. The quintessential iteration is going from product requirements to testing an initial prototype then jump back to requirements development based on what you have learned. The first iteration is typically the most expensive and time consuming.

The path to production starts with defining the product requirements, designing the product, then prototyping and finally on to manufacturing.

Requirements, Specifications, and Test

Requirements Development

The engineering process starts with a product requirements document (PRD) typically developed by the product manager with input from everyone from engineering to marketing to customers. Having a well-developed PRD is critical before starting the engineering process. A poorly-developed PRD will cause unnecessary iterations in the engineering process as the deficiencies in the PRD are discovered. These will be both costly and time-consuming. It’s best to do the product requirements homework up front.

Specifications Development

The first engineering step is to take the PRD and clarify as many details as possible about the use and performance of the product. This is documented in an engineering specification (a specification is basically a requirement that is more “specific” than the product requirement). If we have a requirement of “all day battery life”, the specification needs to define what “all day” means in terms of hours and usage of the product.

Functional Test Plan Development

The next step is to outline a functional test plan. The plan will eventually define a step-by-step procedure that describes how to test the product and verify it meets each requirement in the PRD. The details of the plan will be filled in once the design is complete.

Example

The following is an example of a few requirements with their accompanying specifications and test actions. Requirements should be numbered and have corresponding specifications and test steps.

Note, not all requirements will necessarily have additional specifications.

Requirements

- All Day Battery Life

- Fits in your pocket

- Waterproof

Specifications

- Battery must last 12 hours with 4 hours of active usage

- Dimensions must not exceed 4x4x0.5 inches

- Must conform to IP67 waterproof standard

Functional Test Outline

- Put device in active mode for 4 hours then sleep mode for 8 hours and log battery levels

- Measure device to ensure it meets the specified dimensions

- Place one meter under water for at least 30 minutes, retrieve and check for damage

Important Tip! These documents are both super boring and super important. It will be well worth developing and maintaining these documents to ensure you don’t miss anything when transitioning from development to production.

Design

Architecture Development

The high level architecture diagram identifies which technologies will be used to meet the requirements.

The diagram above shows the architecture of the Stratify Toolbox. It calls out the computing platform (STM32F7) and the basic functions.

On the first pass of the architecture diagram, it may not be clear which components to use. In this case, options are evaluated for best fit.

Component Evaluation and Selection

Component selection is a big driver in balancing out development costs, time-to-market, and bill of materials costs.

Let’s take the development of a wifi router as an example. On one extreme, you could buy and re-brand a fully functional wifi-router. This minimizes development costs as well as time to market but is expensive to produce.

On the other extreme, you could not use any off-the-shelf components and develop your own resistors, capacitors, processors, and radios which would have enormous development costs and take many years to complete but would produce a highly differentiated product that could be mass produced at the lowest possible cost.

If you are releasing the first generation of your product, it is wise to stay as close to the off-the-shelf extreme as possible. This will minimize time-to-market and allow you to quickly improve and refine the product with customer feedback. As you move to the next generations of the product, you can use customer feedback to implement the most important features.

iPhone Case Study The evolution of the iPhone is a good example of this multi-generational process. The first iPhone used a CPU from Samsung (specified by Apple). The iPhone 4 used an Apple designed chip. Apple continues to replace third-party components with internally developed ones as it pushes the boundaries of innovation.

Creating Design Documents

Once the components are selected, the design documentation begins. For circuit boards, this means schematic capture and PCB layout using software such as Altium. For mechanical parts, it means 3D modeling software (e.g., Solidworks).

The software will generate 3D files, gerber files, BOMs, and assembly data that is used for prototyping.

Initial efforts to develop firmware and software can also start happening during this time. However, there are limits to what can be achieved without a prototype.

Prototyping

Prototyping includes building a few units for test and evaluation purposes.

PCBs

For circuit boards, it typically takes three weeks to build boards and test for basic functionality.

Mechanical Parts

Mechanical prototyping schedules vary depending on the process used. The most common approach for the first iteration is to have the parts 3D printed which can usually be done in less than a week.

Integration and Test

Once the boards are basically working and the mechanical parts fit together, the PCBs, firmware, software, and mechanical parts all need to be integrated and tested. This is the time to fill in the details of the functional test plan and identify what is working and what is not.

This is Where Things Go Crazy! On the first iteration, there are always problems. The number and type of problems that you run into are so varied and numerous they are impossible to predict. Many problems can usually be solved by “hacking” the prototype. This involves modifying the circuit by hand to get things working and modifying the mechanical prototypes using a Dremel-like tool. The best approach is to methodically go through each point in the test plan and evaluate what is working and what is deficient.

Iterate

Once testing and integration is complete, it might be time to revert to an earlier step in the engineering process and continue forward based on the knowledge gained from testing.

For example, if the battery life testing results in less than a full-day of battery life, the process reverts back to the design stage to modify the circuit and then continue to build and test new prototypes.

Manufacturing

Once the product passes the functional test plan, it is time to move on to production. The manufacturing process will drive additional iterations in the engineering process. The contract manufacturer may request changes to the design in order to facilitate mass production.

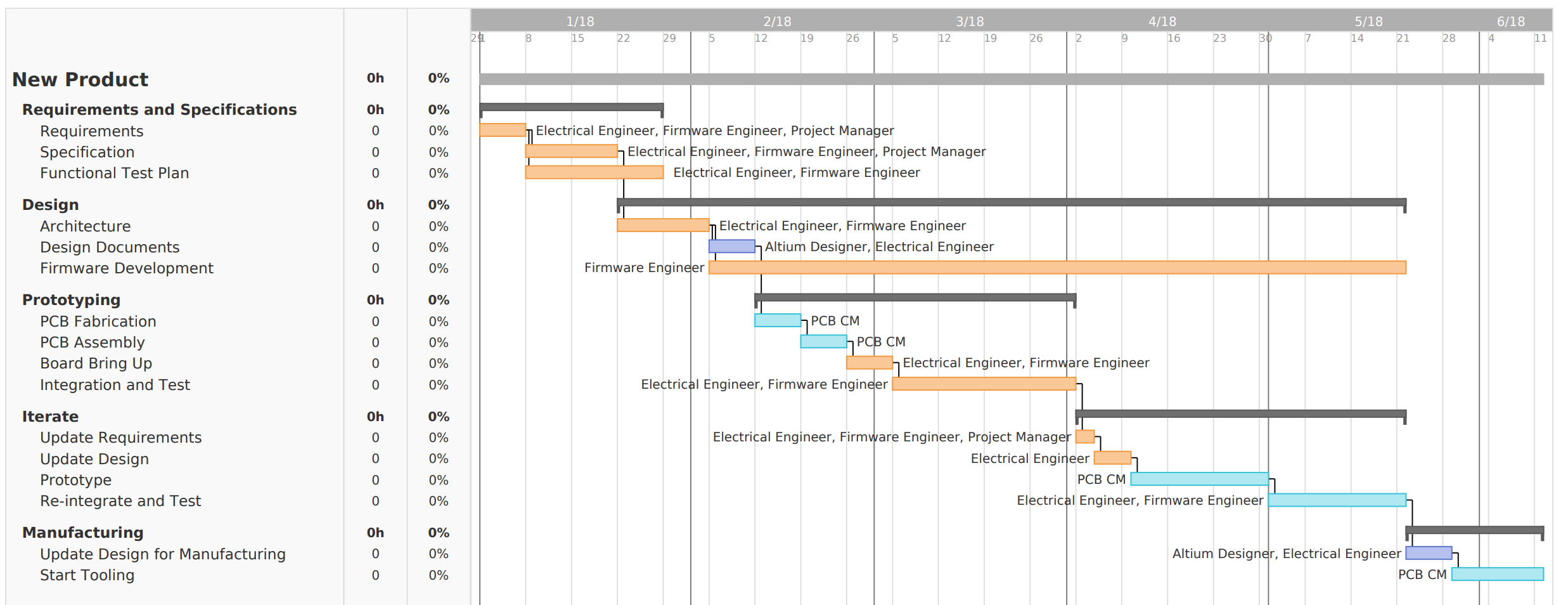

Sample Schedule. The sample schedule below shows how the process can play out if well managed. The schedule includes the initial iteration which takes about 3 months to build and test the first prototypes. A second iteration takes another 6 weeks or so before the product is sent to manufacturing. Depending on the complexity of the project, more iterations may be needed. Subsequent iterations typically take less time but it is difficult to get below 3 weeks for an iteration where PCBs are being built and assembled.

Final Words

Remember the engineering process is iterative. Don’t plan a single iteration. If time-to-market is critical, it is more effective to iterate quickly than to try and get everything right the first time. The most will be learned in the integration and test phase after prototyping.