The Problem with malloc()

In C and C++, memory is either statically or dynamically allocated using the heap or stack.

These articles are helpful in understanding the concepts herein:

| Where/How | Static | Dynamic |

|---|---|---|

| Stack | none | local function variables |

| Heap | bss/data | malloc() |

If we look at a small C program, we can see all of these scenarios:

#include <stdlib.h>

//Static memory allocated on the heap

//uninitialized global data goes in bss

//initialized to zero

int bss_value;

//a copy of the data goes in flash

//and is copied to RAM at startup

int data_value = 10;

int main(int argc, char * argv[]){

//allocated at runtime on the stack

//uninitialized stack variable has undefined value

int dynamic_stack_variable0;

int dynamic_stack_variable1 = 10;

//allocated at runtime on the heap

//uninitialized block has undefind content

void * memory = malloc(512);

return 0;

}

What is the problem with malloc() (aka the dynamic heap)? malloc() has both performance and efficiency problems compared to the stack.

Performance

Allocating data on the stack is ultra-mega-lightning-fast. The CPU adjusts the stack pointer in a few CPU cycles, and the memory is allocated. malloc() takes hundreds to thousands of CPU cycles. Consider the following scenario.

//A

const size_t chunk_size = 128;

void * one = malloc(chunk_size);

void * two = malloc(chunk_size);

void * three = malloc(chunk_size*2);

void * four = malloc(chunk_size);

//B

free(2);

void * five = malloc(chunk_size*2);

//C

free(four);

void * size = malloc(chunk_size*2);

//D

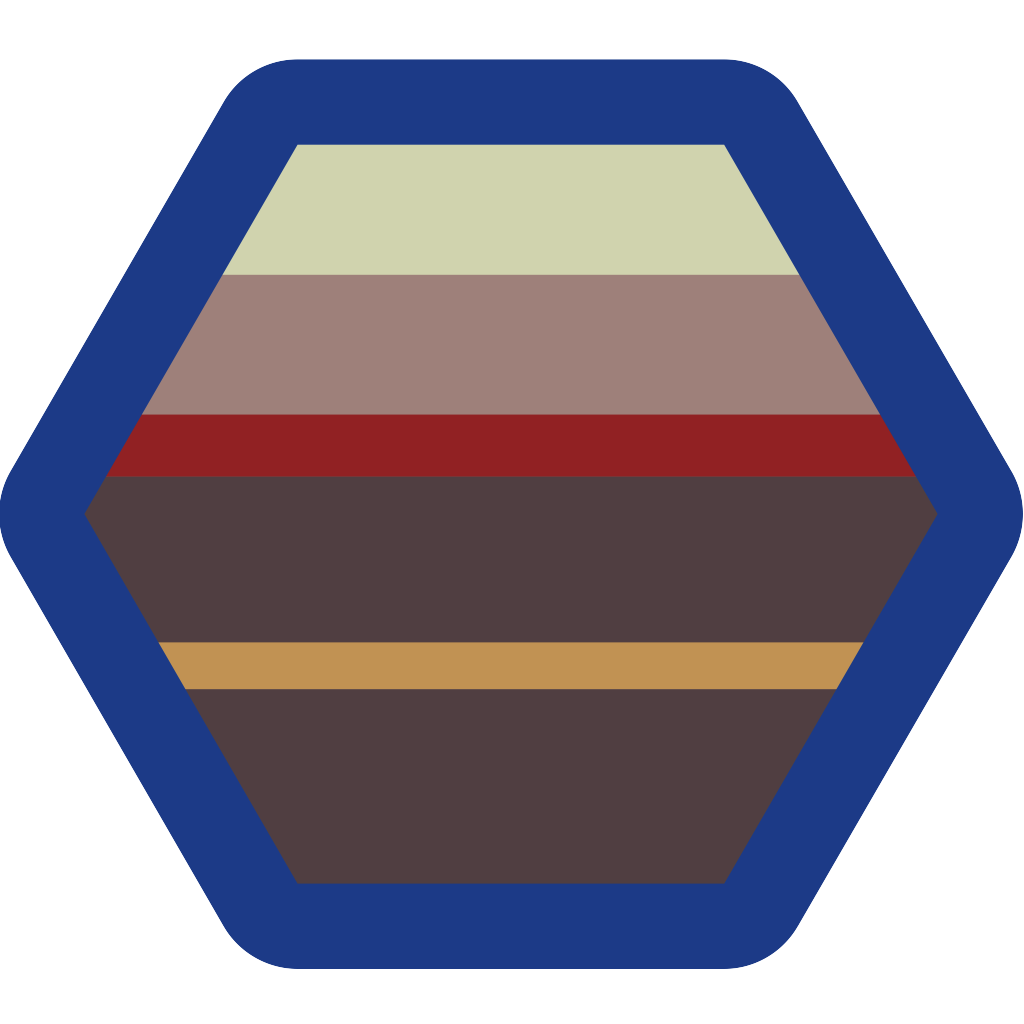

A: the heap starts in stateA. The system has not allocated memory to the dynamic heap. Thestack guardis a memory-protected section that causes a fault before the stack collides with the heap.B: to allocate regions1to4, the system needs to move thestack guardthen start adding the memory to the allocation table (or linked list)C: region2was freed and region5was allocated.free()happens faster thanmalloc()because it simply needs to mark the memory as free. Region5won’t fit where region2was freed, so the system adjusts thestack guardand allocates5on top.D: A similar sequence happens when4is freed and6is allocated.

That is, managing the dynamic heap takes way more than a few CPU cycles.

Efficiency

The stack packs data tightly. If it weren’t for memory alignment, it would be 100% efficient. malloc() is never 100% efficient. If you allocate small memory chunks, malloc() will be less than 50% efficient. With very large chunks, it will be close to 100%. If you have small and large chunks, you will run into fragmentation problems which are discussed below.

malloc() needs to maintain a table or linked list to keep track of how the memory is organized. Assuming a linked list, a malloc() entry might look like this (assumes a 32-bit system):

typedef struct {

size_t size; //4 bytes

void * next; //pointer to the next entry

uint32_t status; //free or allocated

} malloc_entry_t;

If you allocate a four-byte word, it will occupy 16 bytes on the heap (25% efficient). Some malloc() implementations (including the one on Stratify OS) enforce minimum spacing between linked list entries to prevent fragmentation. This minimum spacing varies but is in the 128-byte range. If you allocate one byte, it will occupy 128 bytes on the heap (0.7% efficient). Converserly if you allocate 2036 bytes. It will have 2036/2048 = 99.4% efficiency because 2036 + sizeof(malloc_entry_t) is 2048 AND 2048 % 128 is zero.

Fragmentation

If you allocate/free blocks of memory with large disparities in size, the malloc region will get fragmented. You can see this in the diagram above where state D has holes where 2 and 4 were freed. Ultimately, one of two things happens with fragmentation:

- Your

malloc()region reaches a steady-state and stops growing before you run out of memory. 😁 - Your

malloc()region runs out of memory and crashes before reaching a steady-state. 😠

Avoiding Pitfalls

There are three ways to avoid the major drawbacks of malloc().

- Never use

malloc(). Allocate all memory either statically at compile-time or using the stack. - Never use

free(). Usemalloc()during startup, but neverfree()the memory and never usemalloc()after startup. - Use

malloc()andfree()minimally as needed BUT never in a performance-critical area AND ensure through testing that you reach a steady state before running out of memory.

If you opt for (3), you should rely as much as possible on (1) and (2) to minimize the amount of potential fragmentation in your program. The tips that follow are ways to use the stack or static heap when you might be tempted use the dynamic heap.

Variable Length Arrays

Using variable-length arrays in C and C++ (14 and beyond) is one way to avoid malloc().

void function(size_t size){

uint8_t buffer[size];

//use buffer within this function only

}

Max Buffer Size

In most cases, malloc() is used when the buffer size is unknown at compile time. But if you know the max buffer size, you can use that instead.

class FilePath {

public:

//do this

void set_path(const char * path){

strncpy(m_path, path, PATH_MAX);

m_path[PATH_MAX] = 0; //guarantee null terminator

}

//don't do this

void set_dynamic_path(const char * path){

const auto length = strlen(path);

m_dynamic_path = reinterpret_cast<char*>(malloc(length));

}

private:

//I know a valid path will always fit in PATH_MAX

//If the FilePath instance is on the stack, m_path will be also

char m_path[PATH_MAX+1];

//path length is unknown at compile time

char * m_dynamic_path = nullptr;

}

The End

malloc() has major performance and efficiency penalties compared to allocating data on the stack. You can still use malloc() in constrained systems but:

- Use the stack and static heap as much as possible. Learn better ways to use the stack/static heap.

- Use

malloc()at startup or in other non-performance critical code sections only - If you must use

malloc()throughout runtime, do so minimally, AND test, test, test!

If you need more ideas on avoiding

malloc(), look into C++ PMR concepts and/or memory pools.